So What Happened to Aaron Burr After That Duel?

After fatally wounding former Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton in America’s most famous duel, Vice President of the United States Aaron Burr went home to have breakfast.

The months and years following the duel would see the dismissal of two murder indictments and a treason trial for a brazen (but confusing) conspiracy to deliver a chunk of the Louisiana territory to England. Or maybe to Spain. Or maybe to create an independent nation. Or maybe to invade Mexico.

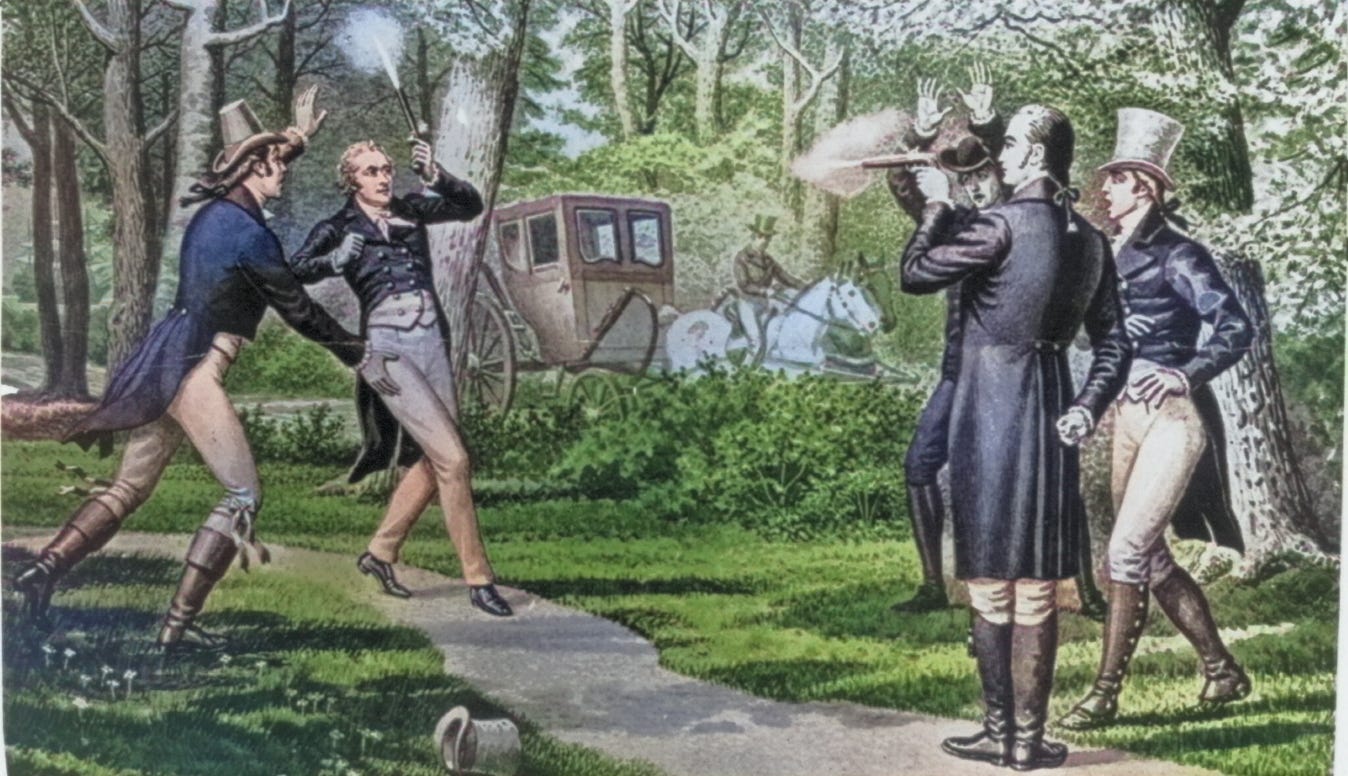

But let’s start with the duel on July 11, 1804. The encounter in Weehawken, NJ, on a small plateau above the Hudson River, ended decades of political rivalry between Burr and Hamilton that had degraded into personal hatred.

By 1804, Burr’s political career was falling apart. After his second-place finish in the presidential election of 1800 — a race decided by the House of Representatives after Burr and Thomas Jefferson had tied in the Electoral College — Burr had been serving as Jefferson’s vice president. Burr blamed at least part of his defeat on Hamilton’s lobbying against him before the Congressional vote.

Given their competing philosophies and personal animosity, Jefferson made it clear Burr would not be his choice for vice president in the 1804 election. Burr tried to save face by running for governor of New York in April 1804, but Hamilton’s anti-Burr lobbying again hindered his ambitions and contributed to a resounding defeat.

Burr demanded an apology after learning about unflattering remarks Hamilton had made about his character. For his part, Hamilton declined to apologize, explaining (more or less) that his remarks were true, he meant them, and would gladly say them again if asked to. This statement essentially locked them into dueling.

After Hamilton’s death, Burr was indicted in New York and New Jersey for murder and for dueling (everything wasn’t legal in Jersey). Before he could be tried in New York, Burr fled to Georgia and took sanctuary at a plantation owned by former Senator Pierce Butler.

Burr Returns

For most people, fleeing two murder indictments would probably inspire them to retreat from public life. But not Aaron Burr.

Burr returned to the Senate in November 1804 to oversee the impeachment trial of Supreme Court justice Samuel Chase (who was acquitted). Burr resigned as vice president and delivered a farewell address in the Senate in March 1805.

His New Jersey indictment was dropped, largely due to the intervention of political connections.

Burr’s Interlocking Conspiracies

We next find Aaron Burr roaming the Louisiana territory conspiring with representatives of England and Spain, mercenaries, and businessmen interested in annexing Mexico. Burr’s goals for these activities are hard to unravel because Burr apparently launched conspiracies with conspiracies, making competing promises to whoever he was conspiring with at the moment.

For example, Burr was negotiating with the British minister to the United States to deliver portions of the sparsely populated Mississippi Valley to England. The minister didn’t know Burr was promising the same territory to Spain. He was also working with New Orleans businessmen who hoped to invade and annex Mexico.

One of Burr’s co-conspirators was General James Wilkinson, who also had a colorful past and questionable ethics. Wilkinson had long conspired with Spain, including discussions in the 1780s for Kentucky and Tennessee to leave the United States and join Spain. Burr arranged for Wilkinson to be appointed territorial governor of Louisiana.

Burr traveled the territory, recruiting a handful of disaffected military leaders and a few hundred volunteers willing to join the conspiracy in return for tracts of land.

But Burr and his co-conspirators were indiscreet enough that, in an era when news spread on horseback, word of his plans appeared in several Eastern newspapers. Afraid of being arrested, Wilkinson revealed the plot to Thomas Jefferson.

In November 1806, Ohio and Virginia militia took over an Ohio River island where Burr had established a training post for his army. At the time, Burr was away recruiting supporters.

Burr was arrested in February 1807 in present-day Alabama and returned to Richmond to stand trial for treason. During the trial, Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that the definition of treason in the U.S. Constitution required an “overt act” of war or support for an enemy. Since Burr’s plot had been disrupted before he could carry out an overt act, he was acquitted.

Facing public enmity and an array of civil litigation, Burr sailed to England. Five years later, he returned to New York. With the War of 1812 looming, the long-outstanding charges for the Hamilton duel were dropped.

Burr later remarried and practiced law. He died on September 14, 1836, in a Staten Island boardinghouse.